The rather racy poster for a German conference on Perpetua. (Source)

So my last entry, about Vibia Perpetua, first diarist in human history, left you all hanging. (Yes, I know… you couldn’t sleep a wink for thinking about it.) I had gone over the facts of her life as far as we know them, which could roughly be summarized thus: a young, upper-class Carthaginian woman is arrested by the Romans and thrown in prison to be fed to wild beasts, and while imprisoned, winds up revolutionizing literature as we know it by inventing the diary.

Diarist, Schmiarist. Who Cares?

So… Perpetua was the first diarist. Her work is a virtual treasure trove of juicy historical detail–it tells us a great deal about early Christian communities, life in North Africa in the 2nd century CE, relationships between Roman fathers and daughters, and much more. (1) But, assuming the vast majority of us are not writing doctoral dissertations on Roman Carthage, what real import does her diary have for us?

Oh, Perpetua! Let me count the ways…

First, for the teachers and/or women’s history buffs among us, her diary gives us a tantalizing clue about Roman women’s literacy, and perhaps literary history in general. And then, more broadly, it tells us something about the shift in human consciousness that occurred sometime in the first few centuries CE–a shift towards a more “interior” form of religion that Rudolf Steiner thought was emblematic of the late Greco-Roman era, and of Christianity in particular. More on that below. First, let’s consider the Roman ladies.

Roman Women: Perhaps not as mute as sometimes thought

Because we have so few examples of literature written by Roman women, it has sometimes been supposed, (even by scholars who should know better) that most of them were illiterate. Or at best, literate, but not writers of anything other than the occasional letter. That’s simply untrue. There’s actually a good deal of evidence that many, if not most, upper class women could read and write. (2) However, though we have lots of references to the fact that they could write, we don’t have a lot of evidence for what they actually did write. Even for the women who were publicly recognized as authors, we have depressingly few surviving texts. Later male copyists were not kind to women.

With Perpetua, we have a very rare window in. And here’s what’s interesting about her: neither she nor anyone else in the text thinks it’s odd that she took the time while in prison to write down the ins and outs of her daily life. In other words, no one is surprised that she keeps a diary.

Without Perpetua, would there have been a Margaret? For centuries, women have reflected on faith, dreams, and daily life in their diaries.

This tells us that writing, and perhaps even diary-keeping itself, was something a woman of her social position might normally be expected to do. We simply can’t know whether other Roman women kept diaries that have not survived to us, or whether Perpetua’s diary was a one-time flash of brilliance emitted before her bloody end. But it’s an intriguing thought, and certainly worth noting, that if none of her contemporaries remarked on her diary-keeping, it may indicate that some women did it as a matter of course. (3) Might the diary have been one of those few arenas for writing that even “virtuous” upper-class women were allowed to pursue?

And, even more tantalizing: if diary-writing originated as a specifically “female” occupation (precisely because it was concerned with the minutiae of daily home life and was generally not circulated to the public), is Perpetua’s diary an example of women’s private writing bursting forth to create a whole new genre of literature? We may never know for sure, but Perpetua lets us wonder. (4)

Perpetua Breaks Barriers, Human and Divine

Perpetua’s diary has another, possibly even greater, significance. It gives us a glimpse into the moment when human beings were beginning to think of themselves, and their relation to the divine, in a new way.

Rudolf Steiner, the 20th century philosopher and founder of Waldorf education, described the first few centuries CE as a time when people felt that the gods had somehow become more distant, or less accessible, than they had been in previous centuries. (5) In the ancient world, religion had long centered around acts of offering and sacrifice (including to the king or emperor himself), but for a growing number of people, these acts became less imbued with meaning–perhaps because religion had become increasingly controlled by and connected to the imperial state. They sought new types of religious experiences, ones that were not so intertwined with the power of Rome. I mean, really…once you had an emperor building gold statues of himself as a god and dressing up in matchy-matchy outfits with it, who wouldn’t be looking for a new religion on the block? (BTW, I’m not joking about the statue. Caligula anticipated by about 2000 years the matching outfits beloved by aged Floridians.)

In the first few centuries CE, a number of religious practices arose that offered their adherents something different, something that hearkened back to the religious experiences of ages past, when people felt that the gods had moved in and among the living in more perceptible ways. From magic and alchemy, to revivals of ancient mystery cults, to gnostic sects and relatively new religions such as Mithraism or Christianity–what they all shared was that practitioners felt they experienced the deity (or deities) directly, in an inward way.

Despite featuring a Nordic god, this poster pretty much sums up how the Roman state viewed Christianity. (Source)

Perpetua’s work provides a beautiful example of this movement back towards a personal experience of the divine. And even further: her diary perfectly captures the idea that following God might involve listening to an “inner voice” that could conflict with the outer demands of family and state. This was utterly bewildering to the people around her who were invested in the Roman state religion (including her father). What did she mean by claiming she was obeying God? It was sheer nonsense. To be a pious woman, she had to follow the will of her father and carry out her obligations to the state, including participating in the requisite festivals and sacrifices (and not as bull-fodder). (6) That’s what piety meant: doing what was required of you by the representatives of the gods.

And even more ridiculous to the average “Roman on the street” would have been this: Perpetua’s claim that she (and her god) were somehow victorious when she clearly was not. (7) It simply didn’t make sense to think of being fed to lions as anything other than a defeat–not only of Perpetua, but of her deity. It’s obvious: if your god is so great, how come you’re being gored by that bull? (8)

Perpetua’s diary takes pains to demonstrate how heaven’s logic might not conform to earthly expectations at all–how her arrest and imprisonment (and even her final death) could be evidence of her greater, inward victory. And she does this in a way that is eminently personal. She didn’t write a philosophical treatise on why the Roman state should be dismantled, or a long letter with moral exhortations to fellow-Christians. Instead, she kept a minute account of her day-to-day inner and outer life as an expression of the inner workings of the Holy Spirit.

This was new. And revolutionary. And in my humble opinion, something that she might not have achieved if she had been male. Lots of men (and some women) before her had reflected on the inner voice of God, on what it means to follow God, and on what it means to be a “victor” in God’s sight–usually in the form of philosophical treatises or letters of advice. And plenty had recorded their dreams in temple inscriptions and books of dream interpretation. Still others wrote letters to each other about their daily lives (“Today so-and-so said such-and-such to me; the next day we went to the forum,” etc.) But no one had brought it all together in a diary as “my story” before–a text where inner thoughts, dreams, and experiences of the divine, are interwoven with daily life. It took, perhaps, a Roman woman–someone who was “supposed” to confine her writing to the private sphere–to bring all these different threads together in a text that so perfectly captures the revolutionary inwardness of the late Roman period, and shows how diametrically opposed this new interiority could be to the priorities of the imperial state.

This was new. And revolutionary. And in my humble opinion, something that she might not have achieved if she had been male. Lots of men (and some women) before her had reflected on the inner voice of God, on what it means to follow God, and on what it means to be a “victor” in God’s sight–usually in the form of philosophical treatises or letters of advice. And plenty had recorded their dreams in temple inscriptions and books of dream interpretation. Still others wrote letters to each other about their daily lives (“Today so-and-so said such-and-such to me; the next day we went to the forum,” etc.) But no one had brought it all together in a diary as “my story” before–a text where inner thoughts, dreams, and experiences of the divine, are interwoven with daily life. It took, perhaps, a Roman woman–someone who was “supposed” to confine her writing to the private sphere–to bring all these different threads together in a text that so perfectly captures the revolutionary inwardness of the late Roman period, and shows how diametrically opposed this new interiority could be to the priorities of the imperial state.

This, Perpetua did perfectly. Her diary stands, therefore, not only as a witness to her own particular courage in subverting Roman gender, familial, and imperial norms, but also as a testimony to the way in which a specifically female voice could so eloquently paint a picture of the changing religious experiences of the time.

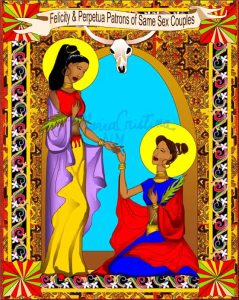

Artist Jim Ru’s interpretation of the “couple” (Source)

Now, just for fun: Who knew? In recent years, Perpetua (along with her slave Felicitas) has become a patron saint of lesbian couples. Given how strange some of the traditional saint associations are (e.g. St. Fiacre, who because he could reputedly heal hemorrhoids, is now patron saint of STDs), Perpetua and Felicitas’ stint as a lesbian couple is probably neither more nor less far-fetched than many others. And it’s nice to think there’s a patron saint for everyone. (Saints Sergius and Bacchus are the patrons of male couples, and there seems to be some evidence that they really were lovers in real life.) Here (and scrolling down through my notes) are some contemporary icons of the happy female couple. The last one is by far the raciest (I gotta keep you reading to the end somehow) It was done way before the LGBT Christian movement gained traction–by a 19th c. male Australian artist who apparently specialized in naked women in chains. As one contemporary blogger writes, it’s what the two women might have looked like as an inter-racial couple sleeping nude in prison.

——-

NOTES

(1) Joyce E. Salisbury does a nice job of summarizing the relationship of Perpetua’s diary to other literary works of her time period, including Hellenistic romances, early Christian tracts and letters, and texts on dreams and dream interpretation. Perpetua’s Passion: The Death and Memory of a Young Roman Woman. New York: Routledge, 1997. pp. 92-98.

Artist Maria Cristina’s depiction of Perpetua and Felicitas (Source)

(2) This website, though a bit hard to read and written from a Christian perspective, does a nice job at collecting many of the ancient Greco-Roman references to literate women in one place. Another excellent (and much more scholarly) resource is I.M. Plant’s book, Women Writers of Ancient Greece and Rome: An Anthology. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004. It’s a great source for teachers, since it collects in one place all the writings of Greco-Roman female writers, and gives a 1-2 page introduction to each figure.

(3) Even the rather grumpy Plutarch, who warned that “a virtuous woman’s speech should be private,” allows his hypothetical perfect female the possibility of speaking and writing privately to her family. Plutarch was a Greek from the 1st c CE who became a Roman citizen, and wrote on a number of topics, including the correct deportment of women. This quote comes from his Moralia, 142c-d. You can find the whole passage online here.

(4) It’s interesting to note that the second diary-like text we have was also written by a woman–Egeria, a Spanish Christian pilgrim who traveled to the Holy Land in the early 380s CE. She wrote to a group of sisters (sorores, who may or may not have been nuns) about her travels in and around Palestine, focusing on her daily activities and the sights she saw. It reads more or less like a travel diary. You can read the whole diary online here.

(5) This dissatisfaction with the state religion and rise of new/revived religious traditions has been noticed by other scholars too–it’s not simply a “Steiner thing.” Writing 50-some years after Steiner, eminent classicist E.R. Dodds characterized the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE as the “Age of Anxiety”–a time when individuals felt a growing division between earthly life and the celestial world, and longed for union with the divine. E. R. Dodds. Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965. Joyce Salisbury gives a great overview of his main arguments in her book Perpetua’s Passion. (pp. 22-32. See note 1 for full reference.)

Artist John Darcy Noble’s rendition of the saints. (Source)

(6) Perpetua, like all Roman women, remained under the control of a male her entire life. Roman women were legally bound to obey the pater familias (legal male head of the family) under the system of patria potestas (power of the father). By Perpetua’s time, most Roman women never left their father’s power, even after they married (though sometimes marriage contracts were written up in such a way that she was transferred to her husband’s authority.) There were occasions in which a woman could be “emancipated” from male authority, but these were relatively rare.

(7) It’s interesting, here, to consider some earlier Jewish texts on martyrdom, including 4th Maccabees (dating from the 1st centuries BCE-1st century CE, before the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE). These texts are in no way diaries, but they do portray the persecution and death of Jews at the hands of Romans as victories–in the case of 4th Maccabees, the victory of the victims’ self-control over their fear.

19th c. artist George Hare’s depiction of a beatific Perpetua and Felicity sleeping in each others’ arms. Robert Mapplethorpe has nothing on this guy. (Source)

(8) Steiner spends some time considering this counter-intuitive argument in one of his lectures, “Three Streams in the Evolution of Mankind,” which he gave in Dornach in 1918. He focuses particularly on the logic of Tertullian, a Carthaginian church father who was roughly contemporaneous with Perpetua, and who may even have been the author of the introductory portion of her diary that was added after her death. For his consideration of the general religious climate of late antiquity, see Lecture One of his work, The Fifth Gospel (1913). Both texts can be accessed through the Rudolf Steiner online archive, here.