My take on the Shakespeareisahipster meme.

So, dear readers, when we last left Enheduanna, we had learned all about her life and times and were about to embark upon an examination of her literary output–a corpus of hymns to various temples and deities that was so sophisticated and psychologically nuanced compared to other writings of the time that the eminent Assyriologist William Hallo referred to her as “The Sumerian Shakespeare.” But given that she preceded Shakespeare by about, oh, 3800 years, it might be more apt to dub the bard “The English Enheduanna.” In any case, don’t just take Hallo’s word for it–read on for why you, too, should care about her work.

Enheduanna’s Literary Career

Enheduanna’s literary output is divided into two main bodies of work: her temple hymns, which were addressed not to individual deities, but to the temples themselves, and her hymns to Inanna, who appears to have been Enheduanna’s favorite goddess. (1) To do justice to Enheduanna’s theology and literary style you’d need to read the poems themselves (we wouldn’t be satisfied with an online synopsis of Shakespeare, would we?). But I’ll try to summarize briefly here the main points as they’re relevant to our work as Waldorf teachers.

First, you should know what the experts (that is to say, Assyriologists) say. They usually relate her poetry to the larger political events of her time, seeing the hymns as a unified body of work that forms part of a political campaign. Each temple hymn, for example, is dedicated to “lugal-mu” (“my king”), and as a whole, the hymns take pains to link the religious centers of Akkad with those of Sumer. (2) In this view, Enheduanna appears as a PR agent of sorts for her father, King Sargon, helping smooth relationships between the two peoples he was attempting to rule. She certainly seems to have been smart enough to be in charge of such a campaign. However, personally, I think that whatever her political motivation, the hymns themselves are so lyrical that we have to take them seriously as religious and literary endeavors, not just cagey political moves. And more to the point, it seems significant that Enheduanna emerges as the first author in history at this point in time. After all, if the hymns were more or less just propaganda, she could have written them anonymously. So why put her name to them? What’s going on?

Enheduanna’s Genius: Going “Meta” in her Poetry

Enheduanna is hereby posthumously presented with Notablewoman’s Certified Genius Award, for services rendered to the evolution of human consciousness

Here’s what’s going on: the woman was a genius. Perhaps the most wonderful moment in all of Enheduanna’s work is when, in one of the Temple Hymns, she names herself and reflects on her own brilliance. But unlike Shakespeare, who immortalized himself and his poetry in Sonnet 18 with the line, “so long lives this, and this gives life to thee,” Enheduanna, wonders not at the longevity of her poem, but at its sheer novelty:

the person who bound this tablet together / is Enheduanna / my king, something never before created / did not this one give birth to it? (3)

The woman was hot and she knew it. And after all, didn’t she have the right to brag a bit? As far as we can tell, no one else had ever thought to put their name down on a literary work before. Basically, Enheduanna went “meta” on her peers–not only did she compose a poem, but she drew attention to the fact that she, Enheduanna, had done it. Of course, even without her name, her work would still retain its striking images and lyric beauty. But her capacity for self-reflection is what really distinguishes Enheduanna. (To hear a four-minute selection of her poetry read in the original Sumerian, click here, then scroll down to the bottom of the page and press play.)

For us Waldorf teachers, Enheduanna’s self-reflection is particularly interesting because she emerges as the first authorial persona in human history in exactly the era Steiner pinpointed as the beginning of human awareness of our inner emotional life. (4) This period, which he called “Egypto-Chaldean,” spanned roughly 2900-750 BCE. Much later during this era we see other individual authors emerge: Shin-eqi-unninni (author of the Epic of Gilgamesh, who is supposed to have lived sometime around 1600 BCE, a full 700 years after Enheduanna), Hesiod, Homer, Sappho, etc. (5) But Enheduanna was the first, and judging from her hymns, she knew it.

Enheduanna’s Complexity: Exploring Human Emotions

In addition to being the first person to identify herself as an author, Enheduanna was also (as far as we can tell) the first person to write about her own inner emotional state. As Steiner notes, cultures prior to the Egypto-Chaldean period did not distinguish so clearly between inner and outer, human and divine, emotional life and bodily experience. And in order to examine one’s inner life, one first has to distinguish between the world “out there” and the world “in here.” As a result, there is very little evidence that earlier cultures engaged in what we might call “navel-gazing”–the propensity to think about and reflect on our own inner thoughts and feelings. What is new during the Egypto-Chaldean period, then, is the growing awareness that human emotional life constitutes a separate realm that is ripe for exploration. Once again, Enheduanna represents a pivotal moment in this unfolding of human consciousness.

We see this new way of thinking most clearly in her description of an enigmatic episode from her life. Apparently, at some point fairly far-along in her career (Hallo places it during her nephew Naram-Sin’s reign), Enheduanna was thrown out of her temple and forced to live in exile on the steppe. To add insult to injury, she was replaced as High Priestess by a man named Lugalunne, whom Enheduanna views as a usurper (whether he was a priest or king is unclear). Enheduanna, devastated, pleaded her case plaintively in her third hymn to Inanna:

truly for your gain / you drew me toward my holy quarters / I the High Priestess / I Enheduanna / there I raised the ritual basket / there I sang the shout of joy / but that man cast me among the dead / I am not allowed in my rooms / gloom falls on the day / light turns leaden / shadows close in / dreaded southstorm cloaks the sun / he wipes his spit-soaked hand / on my honey-sweet mouth / my beautiful image fades under dust / what is happening to me / O Suen [i.e. Inanna] / what is this with Lugalanne?…/ he gave me the ritual dagger of mutilation/ he said/ “it becomes you.” (6)

A Sumerian dagger, found in Woolley’s excavations (Source)

What an image. Can’t you just see the victorious Lugalanne standing in the sacked temple, holding Enheduanna’s chin in his hand, brandishing the ritual dagger before her, and leering sarcastically, “it becomes you”? Ugh. Even 4300 years later, it gives me chills.

But here’s another thing that gives me chills: Enheduanna’s heartfelt, almost diary-like poetry about the events of her life and her internal state–it’s all so very new. It’s amazing to think about, because writing like this is so familiar to us now, even to the point of being banal. To say that “light turns leaden” and “shadows close in” as a way of describing your own depression is no big deal these days. But when Enheduanna was writing, no one else in the history of humankind had ever before thought to put his or her personal experiences and inner emotional turmoil on paper (or clay, as the case may be). Truly astonishing.

Enheduanna’s Dilemma: Old Gods vs. New Gods

Finally, as if inventing authorship and navel-gazing weren’t enough, Enheduanna’s writings show us a shift in the very nature of religious experience itself. Steiner charted this movement from earlier eras, in which humans experienced the divine directly, as coterminous with the world (the world essentially was the divine), to Enheduanna’s time (the Egypto-Chaldean period), when humans began to experience the divine as “other,” or as subtly set apart from the human realm. To use some fancy theological terms, we can see this as an evolution from an earlier pantheism (God is everything) into a later panentheism (God is in everything), the latter of which subtly supposes that God has the option of not being in everything, or that God somehow exceeds and/or transcends everything that we see around us.

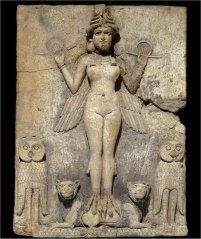

Jungian analyst and scholar Betty De Shong Meador, while seemingly unfamiliar with Steiner’s work, nevertheless nicely situates Enheduanna at exactly this crux of theological history. (7) She notes that Enheduanna’s hymns to Inanna describe the goddess as wearing “the robes of the old, old gods,” and depict her as containing all the fury and contradictions of nature and life itself– simultaneously as maiden, lover, warrior, bringer of birth and death, hunger and famine, growth and destruction. Inanna, in short, represents the last gasp of the old order, when every aspect of life, good and bad, was felt to be embodied in the god(dess). Enheduanna’s first Inanna hymn, “Inanna and Ebih,” relates the story of what happens when the old and new orders collide. (And it ain’t pretty for the new gods on the block.)

In brief, the poem describes an epic confrontation between Inanna and a defiant mountain named Ebih that refuses to “praise [Inanna’s] way.” When Inanna appeals to her father An, the head of the gods, he hems and haws, musing that he finds the mountain’s pastoral charms quite lovely. Ultimately, An refuses to back Inanna in the dispute, referring to her (rather patronizingly, if endearingly) as “my Little One.” At that point Inanna goes ballistic, destroying the mountain in a fit of fury that de Shong Meador translates as “bedlam unleashed.” I won’t reproduce the full passage here, but just in case you ever feel like messing with Inanna, you might want to consider that her vengeance involved hurricane winds, arrows, choking dust, pelting stones, parching drought, poisoned trees, and flames.

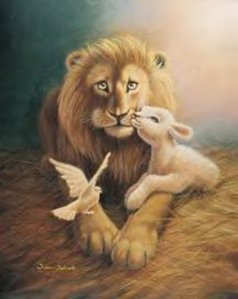

Historically speaking, it’s unclear whether Ebih can be identified with an actual mountain, whether there was perhaps a rival temple or king on said mountain, and if so, if the destruction of the mountain/temple was an actual event (an earthquake, maybe?). (8) What’s interesting for our purposes is that the rebellious mountain is depicted as a bucolic, even paradisiacal place where lions and sheep roam together, much as in the Biblical book of Isaiah. Sounds rather nice to modern ears. But for Enheduanna, the clearly unnatural peacefulness of the mountain marks it out as opposed to Inanna’s way. Nature, like Inanna, encompasses both good and bad, light and dark, birth and death. A holy mountain where lions lie down with lambs is an aberration (an insult, even!) to Inanna. Eternal abundance and peace be damned! Inanna annihilates it, much to Enheduanna’s obvious delight.

Of course, with the hindsight of 4300 years, we can see that the Lady doth protest too much–transcendent gods were the wave of the future, even if Inanna (in the form of her alter egos Ishtar and Cybele) did hang around for another two thousand years or so. Oh, irony of ironies! Precisely the type of introspective self-awareness that led Enheduanna to compose the first authored poem in history, to navel-gaze like the best psychoanalytic patient, to fume about the replacement of Inanna by newer gods–these same capacities were slowly leading human beings further and further away from the religious experiences that had characterized earlier periods of human development, and which Enheduanna held so dear in her beloved Inanna.

It’s important to note here, that Steiner makes no judgment about these different stages of human evolution. We’re not meant to look at Enheduanna’s work and say, “Good girl!” when she demonstrates self-awareness and “Bad girl!” when she has Inanna stomp the bejeezus out of mount Ebih. We’re simply noting, like the best post-structuralists, that human consciousness itself is culturally contingent. That is to say, the fact that Enheduanna was the first person to show us these facets of the human mind is important–she’s the first one because before this time, people experienced themselves and the world differently. Her genius, and her gift to us, was to precisely and poetically capture the moment when humans first looked inward at themselves and wrote down what they saw. Truly, we can say that Enheduanna, the world’s first author, birthed “something that was never before created.”

And that, my friends, is why we should all teach Enheduanna to our students every chance we get.

———-

NOTES

(1) There is some question about whether all 42 of the temple hymns we have really were authored by Enheduanna herself. Apparently, her fame as a poet caused other, later writers to use her name (a frequent practice in antiquity). However, most scholars agree based on stylistic analysis that the vast majority, if not all of them, are hers.

(2) William W. Hallo & J.J.A. van Dijk. The Exaltation of Inanna. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968.

(3) From an online translation by Betty de Shong Meador of Enheduanna’s hymns: http://www.atanet.org/publications/beacons_10_pages/page_15.pdf

(4) It’s almost certain that Steiner didn’t know of Enheduanna’s writings, since Leonard Woolley, the archeologist who first rediscovered her work, did not even begin excavating in Ur until 1922. I have been unable to pinpoint the date that he revealed the disk of Enheduanna to the world, but it appears that his earliest publications (for the Trustees of the British and University of Pennsylvania museums) were in the late 20s and early 30s, after Steiner’s death. It’s even more amazing, then, that Enheduanna’s work fits so nicely with the Egypto-Chaldean period as outlined by Steiner, given that the earliest literature Steiner would have had access to was the Gilgamesh epic, which post-dates Enheduanna by about 700 years.

(5) The first named Chinese authors (many of whom are quasi-historical) appear in the 8th c. BCE; Indian Vedic texts (the earliest of which are believed to have been compiled c. 1500 BCE) were not ascribed to individuals, and the earliest pre-Vedic Indic writing (from the Harappan civilization, which flourished in Enheduanna’s time) has not been deciphered.

(6) Betty de Shong Meador, Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the High Priestess Enheduanna. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2000. pp. 174-175.

(7) I can’t recommend de Shong Meador’s book on Enheduanna highly enough. It is erudite, well-written, and most importantly, really tries to grapple with the spiritual and historical significance of Enheduanna’s work. To be sure, there are moments when she lays on the Jungian analysis a little thick, but as a readable, deep interpretation of Enheduanna (and Inanna, for that matter), it can’t be beat.

(8) William Hallo suggests that Ebih can be identified with the mountain currently known as Jebel Hamrin in Iraq. And he reads the poems not as symptomatic of shifts in human consciousness, but as celebrations of Sargon’s triumphs over the various regions he conquered. William W. Hallo. The World’s Oldest Literature: Studies in Sumerian Belles Lettres. Brill, 2010. For the google book reference, click here.