Well, it’s been two full years since I last updated this blog, and if it weren’t for a helpful kick in the ass from Ugo in Florence, I’d probably still be hiding behind mounds of schoolwork trying not to think about how badly I need to get back to this site. Thank you, Ugo! You rock!

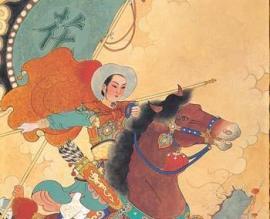

Portrait of Catalina in her “Lieutenant’s” clothes, by Spanish court painter Juan van der Hamen y Gomez de León. (Source)

When I last left you, I promised you a second fabulous Renaissance lesbian, and here she is, though it’s difficult to know whether to classify her as a lesbian, a trans man, both, or none of the above. After giving it much thought, I think I’ll settle for “badass queer,” because that, she definitely was. World, meet Catalina de Erauso, aka “The Lieutenant Nun,” (1) who spent the great majority of her life living as a man, having dashing adventures (both in and out of the bedroom), and who ultimately successfully petitioned both the Spanish court and the Pope himself (!) to recognize her as a legal male. (3)

Gender Bending in the Renaissance

Now, as anyone even half-familiar with Shakespeare knows, Renaissance literature and theater were full of people and practices that we might now consider genderqueer. From the boy actors who played female roles on the English stage, to literary gender-bending disguises in Shakespearean comedies, Boccaccio’s Decameron, and other Renaissance tales–gender fluidity abounds in the stories and plays of the Renaissance. And there are tantalizing indications that though in some ways gender roles were more fixed than they are today, then as now, people found ways to express themselves in non-gender-conforming ways. We saw an incredible real-life example of this in the last post, which looked at Splenditello, the truly fabulous male alter-ego of a Florentine Renaissance nun, Sister Benedetta Carlini.

Catalina had some big ones. (Source)

However, even among the wide variety of literary and true-life stories of Renaissance gender fluidity, Catalina’s story stands out. First of all, talk about cojones! This woman had no problem filling a pair of breeches, as her story will make amply evident. Second of all, like Sister Benedetta’s story, Catalina’s tale provides us with a rare glimpse of real-life lesbian relationships during the Renaissance–though, notably, like Benedetta, she engaged in these romances while in her guise as a man. And last but not least in the list of reasons we should care about and study Catalina: much of her tale takes place in the frontier of New Spain (modern-day Central and South America), so her tale provides a window into some of the ways that gender figured in that tragic period of history when the genocide and epistemicide (3) of an entire hemisphere was in full swing. As her story makes clear, the nascent, transitional social systems in the New World opened up gaps into which someone like Catalina, who wanted to reinvent herself, could slip and even flourish.

So…on with her story.

Catalina’s Early Life

Catalina gives us an account of her childhood in the autobiography she wrote later in life, when she had achieved international fame for her exploits. (4) Many (though not all) facts from this account have subsequently been verified both in Renaissance times by the Papal and Spanish courts, and by modern scholars.

She was born in the Basque country to a captain in the Spanish military, Don Miguel de Erauso, and his wife, Doña Maria Perez de Galarraga y Arce–sometime in the mid-1580s-early 1590s. (5) She seems to have been from a large family, as she was constantly bumping into various brothers in far-flung places on her many adventures. At the age of four, she was placed in a convent along with two sisters. Her maternal aunt was the prioress. She remained there until the age of 15, when she was due to take her vows. At that point, the resentful Catalina, who had been singled out for a beating by a much older novice, seized a moment when all the other nuns were at prayer (Catalina had conned her aunt into thinking she was ill), grabbed a needle and thread, some coins she found lying around, stole her aunt’s keys, ran out the door, into the streets and up into the woods surrounding the convent. As a cloistered nun, she hadn’t been outside the convent since she entered as a toddler, so at first she wandered aimlessly, her only goal to avoid recapture.

You knew I wouldn’t be able to get through this post without a Mulan picture, didn’t you? (See the whole movie sequence here.)

From this exciting beginning, Catalina’s tale gets more and more incredible. She hid for three days making herself men’s clothes (pants and a shirt) out of her habit and undergarment. Then she chopped off her hair and headed for a nearby town.

There, in a scenario that would repeat itself many times in the years to come, Catalina’s natural charisma seems to have taken over, because a kindly gentleman (who happened to be married to her mother’s cousin, but didn’t recognize her) took her in, clothed her as the boy he believed she was, and put her up. She only left three months later when he wanted her to study Latin, she refused, and he hit her.

Having left the gentleman’s house, she went to the king’s court and, calling herself Francisco de Loyola, found a position as a page to the king’s secretary. (6) According to Catalina, one day she witnessed her own father come to the secretary’s house as part of his ongoing search for her. She encountered her dad in the doorway, but he didn’t give her a second glance. This too, is a theme in Catalina’s biography–the way that, dressed as a man, she could pass unnoticed among even her closest relations. That evening she decided her situation was too precarious, so once again she made off in the middle of the night, this time landing, after some time, in Navarre, as the page to a knight of Santiago. In her two years of travels with him in and around Spain, she one day attended mass at her old convent, where her mother was in attendance and apparently looked directly at her without recognizing her.

How Did She Do It?

By this time Catalina was at least 17-18 years old, and one might think her femininity would be harder to disguise, but she apparently had her means. The Spanish pilgrim Pedro de la Valle, whom met her later in life when she was at the Pope’s court in Rome, gives us some sense of her physique when he remarks that she was tall for a woman, and had confessed to him that she used some sort of very painful poultice or herbal remedy given to her by an Italian to “dry up” her breasts. (7) This latter comment is perhaps one of the few testaments we have about pre-hormone therapy “transition” methods.

The drag “mother” is a time-honored tradition. Did Catalina have a drag father? Seems like she may have, though I doubt he was as fierce as RuPaul. (Source)

To me, what’s fascinating about this little bit of side commentary by de la Valle is that it both implies that Catalina confided her secret early on to another man (maybe a local apothecary?), (8) and also that he gave her some sort of remedio that was in common use at the time. Which raises a few questions: Exactly how many people out there were looking to reduce their breast size and/or disguise themselves as men? Clearly enough so that breast reduction herbs were something an Italian medical professional might have in his repertoire. (9) And furthermore, how did Catalina know to trust her herb-wise mentor with her secret? As with so many details of Catalina’s tale, we just don’t know. Unfortunately, this is the only mention we have of the mysterious Italian and his gender-bending recipes. In any case, the poultice seems to have worked. What is certain is that by her late teens/early adulthood, she was successfully living as a man in the highest echelons of Spanish society, and that no one ever seems to have questioned her identity as a man. Even when she was eventually discovered, it was due to her own (unforced) confession rather than the fact that someone had suspected her of being a woman.

“Well,” you might be thinking, taking a break and scrolling back up to the title to this post. “This is certainly the Renaissance, and Catalina seems pretty boss, but really, I was promised lesbian love scenes. Where are the lesbian love scenes?” Hang on, folks, because the ride is just getting started. If you think living successfully as a trans man in Renaissance Spain was badass, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

Catalina in the New World

Jay-Z wasn’t the only hustler, baby. Catalina was no slouch herself. (Source)

To pick up Catalina’s story, she once again ditched her patron on a whim (perhaps because of that close call with her mother), and this time, headed for New Spain. The Spanish colonies were where Catalina really got down to the business of fully owning and embodying exactly what it meant to be a virile young Spanish gentleman. Or some might say, a cad. When she eventually confessed her true identity to the Bishop, Catalina summed up her time in the New World by saying:

I traveled here and there, embarked, disembarked, hustled, killed, maimed, wreaked havoc, and roamed about, until coming to a stop in this very instance, at the feet of Your Eminence. (10)

I don’t know about you, but to me that reads like the résumé of an original gangsta.

Case in point: Catalina had arrived in the New World as a cabin boy on a ship belonging to (of all people) her uncle, who in a now-familiar pattern, did not recognize her, but quickly adopted the young man as his protégé. Catalina admits that the uncle was very good to her, but in the end, her ne’er-do-well instincts took over. Upon docking in Panama, their last stop before the return trip to Spain, she clubbed him over the head while he was sleeping (!) and made off with 500 reales. (BTW, from what we can tell, her nom de guerre changed at this point–she used many throughout her remarkable life, but it appears as though this may be the moment when she changed from Francisco de Loyola to Alonso Díaz Ramirez de Guzmán.)

Just as I was going to press I found this AMAZING website featuring “princesses” too bold/quirky/badass to make Disney’s cut. Catalina’s among their picks, obvs.

After a dramatic shipwreck and another bout living with yet another patron who outfitted her with not only clothes and a business, but slaves as well, Catalina/Alonso found herself in a pickle. Having slashed the face of a local dandy in a sword fight, (10) she was thrown in jail. The only way out, according to her patron, was if she (being to all parties concerned a “he,” of course) married the patron’s own mistress, whose niece was, in turn, married to Catalina’s victim.

Confused? Join the club. Shakespeare couldn’t invent better hijinks than these. Basically, the patron’s brilliant idea was to create an alliance between the two feuding families by having Catalina/Alonso marry his own (i.e. the patron’s) lover. That way the boss would have a forever bond with his mistress, the mistress would have the income and security of a marriage (which the boss, being already married, couldn’t give her), and the blood feud between Catalina/Alonso and the young man she mutilated would be resolved through the marriage, thereby freeing Catalina/Alonso from prison.

Now here’s the interesting bit, as far as lesbian history goes. From this first mention of the boss’ lover, Catalina/Alonso’s tale basically reads more or less as a series of seduction narratives and fight scenes, in which the protagonist is taken in by patron after patron (sometimes patronesses as well), only to become inescapably attractive to a young woman, usually either the daughter or niece of the person who is hosting her. Catalina/Alonso always seems to enjoy the company of the lady, and to participate quite willingly in all sorts of caresses and fondlings. Only when events climax (as it were) in the woman’s proposal of marriage does the young Alonso flee, often leaving a substantial promised dowry behind. In other words, it appears as though Catalina/Alsonso actively participated in all the courting and foreplay of the relationship, only deserting her lover when her male alter-ego was about to be found out.

The Juicy Details

Don Juan could have learned a thing or two from Don Alonso, Catalina’s alter ego. (Source)

The story itself makes great reading in the tradition of all swashbucklers, and I encourage you to read it for yourself, which is easily done online. (You can read it in about an hour, and really, anything that includes cross-dressing, lesbian affairs, numerous rapier duels, a torture scene, and a trans-friendly Pope should be on your “must-read” list.) Here are just a few excerpts, though, of the parts that most directly address Catalina’s relationships with women. These should give you a sense of both what is said and unsaid in her narrative. Her tone, as she describes these encounters, makes it clear that she fancies herself quite the Don Juan. (Or rather, given the chronology of the two, that Don Juan may have fancied himself quite the Don Alonso.) She writes:

I used to slip out by night to that lady’s (i.e. the above mentioned patron’s mistress) house. There she caressed me passionately and, feigning fear of the police, begged me not to return to the church [where Catalina had sought sanctuary] but to stay there. One night she even locked me in and declared that in spite of the Devil I had to bed her. She held on to me so tightly that I had to pry her hands loose to get away.

And about Catalina’s/Alonso’s next conquest:

At the end of nine months he (i.e. Catalina/Alonso’s new patron) informed me that I should seek my living elsewhere. The reason for this was that he had two young maidens living in his house, sisters of his wife, and with whom (and above all with one who was especially fond of me) I used to frolic and fool around. And one day he happened by a window and saw us in the parlour. Reclining in her petticoats, she was combing my hair, our legs entangled. He heard her telling me that I should go to Potosí and earn money so we could get married. He withdrew and summoned me shortly. He questioned me, settled accounts, and I left.

And again, this time with her own brother’s lover (how she came to be the best friend of her brother, who didn’t know her identity, and how she eventually killed him in a duel after he found her sexing up his girlfriend, you will have to find out for yourself):

I remained with my brother as his aide, dining at his table for nearly three years without his ever realizing anything. I went with him sometimes to the house of a girlfriend he had there. Other times I went there without him. He found out about this and took it hard, telling me to keep away from there. He lay in wait for me and caught me at it again. When I came out, he attacked me with his belt and injured my hand.

Like many famous lovers, Catalina was adept at juggling the attentions of two women. (Source)

And my personal favorite, the time that she juggled two different proposals at once by claiming that the gifts given to her by one prospective bride were really a wedding gift for the impending marriage to the other. (She wound up dumping both girls just before the weddings.) That story contains the line in which Catalina comes the closest as she ever does to declaring her sexual orientation outright, when she writes that one of the girls who desired her was “contrary to my taste, which was always the pretty faces.” (11)

Yes, but how Real is her Story?

There is so much more in her narrative that I can’t even begin to summarize it here: multiple duels and stints in prison, bouts of near-death in the high Andes, run-ins with frozen mummies, torture scenes in which she triumphs over the rack, feats of soldierly derring do, etc. etc.

If you are beginning to think to yourself that it is highly unlikely that a woman of her time could have gotten away with such brash deceit, and moreover, that all these adventures both in and out of the bedroom could not possibly have happened to one person, let me assure you that you are not the first to think so. However, by and large, most of the major events in her tale do correlate with actual events, as far as church officials at the time and modern-day scholars have been able to tell. In other words, we don’t know for sure, for instance, whether or not the boss’ mistress really was in love with her and caressed her, but we do know that Catalina/Francisco/Alonso did serve such-and-such a master, that Alonso served in various Spanish forces in the New World, and we can verify that many of the people whom she mentions in the text did, indeed, interact with her. Many of them even supported her (in writing and in person) in her eventual claim for a pension from the Spanish state. Even the medical side of her story can be verified: When she finally confessed her identity to the Bishop in Peru, she volunteered to have a gynecological exam by a panel of matron midwives, who legally vouched for the fact that Catalina did, indeed, have female “parts,” and that she was, moreover, a virgin. (12)

Catalina excelled at “realness.” (Source)

The Bishop’s response to the midwives’ report was sheer amazement–that Catalina could have fooled so many people in so many places, and that, despite having lived among sex-starved men (soldiers, sailors, etc) for so long, she remained a virgin–seemed to him proof of God’s miracles. Rather than arrest her and condemn her for cross-dressing (as had happened to Joan of Arc, for instance), he simply asked her to live among a group of nuns so that she could preserve her chastity. Catalina agreed for the moment, although eventually, she would appeal to the Pope himself in order to continue living her life as a man. (More on that later.)

The Downside of “Realness” and Food for Thought

Like certain drag kings and queens that specialize in “realness,” Catalina/Alonso could quite rightly be said to embody most of the most sought-after masculine traits of her time. This can make her a really fun, and potentially inspiring role model for contemporary trans folk, who need more genderqueer heroes from history included in the textbooks they read. However, in the age of conquistadores, nothing is without its shadow side. For Catalina’s hyper-masculinity includes not just the fun stuff like hose, codpieces, and feathered hats, but also casual misogyny, a hyper-macho sense of easily slighted honor, a tendency to reach for one’s sword at the slightest provocation, and most disturbingly, a truly horrific active participation in the slavery and genocide upon which the Spanish empire was based. Indeed, Catalina/Alonso’s rousing adventures would be fun and games on the order of an old Errol Flynn movie if it weren’t for the very disturbing scenes in which she, like most Spanish soldiers, not only engages in, but positively brags about her triumphantly genocidal tactics against the indigenous population. In by far the most troubling scene in the book, her military party kills a twelve-year-old Indian boy who shot an arrow at them from a tree, and then later massacres his village, boasting that “a gutter of blood like a river flowed down through the place.”

Like the scene depicted here, Catalina describes one of her party’s raids against indigenous groups as culminating in a “river of blood.” (Source)

Catalina/Alonso was no innocent bystander, folks. For you teachers out there, this should be made abundantly clear to the students whenever we are teaching her. Part of what makes Catalina so great for the classroom is that her story offers us both a way to celebrating early LGBTQ heroes AND a way to shine a light on the heinous human rights abuses of the time period.

So because I always like to be practical, as well as (hopefully) inspiring, here are some suggestions for classroom discussion. For those of you who just want to get on with her story, you can just scroll down to continue her tale below.

Questions for Discussion

- How did Catalina perform her gender?

- What did it mean to be a man in her time, and how well did she embody those ideals?

- Who needs to be put down, pushed aside, or altogether obliterated in order for Catalina to seem “manly”?

And taking off from this point, one could extend the discussion further by asking:

- How do we all perform gender in our daily lives?

- What negative sides are there to our own performances?

Are there certain groups that must be dominated or put down in order to achieve “realness” of a particular gender role? (e.g. The use of “bitch/ho” in certain rap subcultures to create a hyper-masculine African-American persona, or the class-based insult “ratchet” to cast aspersion on a woman’s femininity)

Are there certain groups that must be dominated or put down in order to achieve “realness” of a particular gender role? (e.g. The use of “bitch/ho” in certain rap subcultures to create a hyper-masculine African-American persona, or the class-based insult “ratchet” to cast aspersion on a woman’s femininity)- Are there certain subgroups of people excluded from embodying certain roles? (e.g. Are gay or East Asian men considered “real” men in the media? Can a dark-skinned, heavy woman be “truly” feminine to Madison Avenue standards?)

- Must certain groups be abolished outright or given fewer freedoms as part of some other group’s gender performance? (e.g. conservative groups that believe gay marriage threatens heterosexual marriage, and so must be prohibited)

- And finally: Can we find ways to embody our own preferred gender role without engaging in the harmful stereotypes and practices that can accompany it?

If we play it right, Catalina’s story can become a springboard to much wider discussions that may help our students consider the intersection of power dynamics between gender, race, class, and ethnicity (among other things) in their own lives.

Catalina’s Significance

So in addition to her usefulness as a touchpoint for issues of cross-platform oppression, what makes Catalina so special? Other than her setting during the Spanish conquest, what sets her apart from other famous cross-dressing women like Mulan and Joan of Arc?

I’ve thought about it and researched quite a bit, and here’s what I’ve come to:

Catalina/Alonso is important because she is (as far as I can tell) the first case we can find of a person going against deeply ingrained gender norms in order to successfully live out her life as a member of another gender for no other reason than that she wanted to.

Phew! That’s a mouthful. Let’s unpack some key phrases.

A Roman Archigallus, a MtF priestess of the goddess Cybele. (Source)

She is the first case: There are plenty of other examples of cross-dressing and gender-bending way before Catalina, most notably the priests and priestesses of a variety of gods and goddesses throughout the Near East, India, Africa, and the Americas from ancient times all the way to the present. Shamans, both ancient and modern, have also often practiced cross-dressing or engaged in other gender-bending acts as a way of reaching the divine. To my knowledge, however, these practices were all undertaken in the context of larger religious/cultural systems that allowed, or in some cases, even encouraged gender fluidity. This is not to downplay their significance in the history of gender identity, but simply to point out that a male-to-female priestess of Cybele, for instance, was engaging in behavior that had a socially sanctioned and ritual purpose, whereas Catalina’s transformation was neither ritualized, nor did it form part of a larger social order that would be recognized by her peers.

Going against deeply ingrained gender norms: Again, even when cultures have very distinct gender roles for men and women, they may have specific proscribed ways of “violating” these norms. I’m thinking, for example, of Indian hijras, or men who dress (and in some cases live) as women. Traditional Hindu culture has very specifically delineated gender roles, that for the most part, are strictly enforced (as they were in the Spanish culture of Catalina’s time.) But unlike the Spanish Renaissance, which had no specific outlet for fluid gender identities, the hijra is a proscribed role for men who wish to take on female characteristics. Similar things could be said for most of the priests, priestesses, and shamans mentioned above. (This of course, is not to deny the very real discrimination that hijras face, but simply to point out that a third category of gender identity is socially recognized.) Not so in Catalina’s world. She was going her own road, without the support of any community, and without any template to follow or specific role to fill.

Successfully lived out her life: As her story makes clear, Catalina lived most of her life as a man without being discovered, doing all those things (soldiering, seducing, dueling, praying, pillaging, traveling) that a Spanish gentleman was expected to do. At no point was she discovered until she chose to reveal herself, and even then, she went on to secure the right to continue living as a man. (More on that below.) This is in stark contrast, to for instance, Joan of Arc, her more famous cross-dressing counterpart, who was burned at the stake for (among other things) wearing men’s clothes.

I think Catalina would approve. (Source)

For no other reason than that she wanted to: Here’s the part that to me, seems so stellar. Catalina wasn’t living as Alfonso because she wanted to save her father from having to fight in a war (a la Mulan), or because she heard voices telling her to defeat the British (a la Joan of Arc), or because she was fulfilling a religious call (like so many priests, shamans, and religious figures from around the world). Nor was she following an already-established pathway to gender difference, as was, say, a traditional two-spirit “berdache” in Mississippian culture. Catalina seems to have chosen to live as a man simply because she wanted to. Whether that desire came out of a deeply felt belief that she really was a man (as many trans people today feel), or because it was simply the most expedient way not to be confined by oppressive female gender norms, is almost impossible to say. We do know this: Catalina insisted BOTH on the fact that she was a woman (and a virgin, at that), AND that she should have the right to be called “Alonso” (or one of her other male names) and live out her life as a man. Just because.

That makes her, in my book, a boss.

Catalina, the Court, and the Pope

So how did Catalina’s story end? Well, once she had confessed her identity to the Bishop in Peru, she was in a tricky legal position. Of all the most pressing issues facing her, the most important, in that time period, was her commitment to the church. If she had ever professed vows as a nun, she was legally obligated to return to her original convent. (In the meantime, because there was really no other option for single, virgin women of a certain age, she was housed temporarily in a convent.) Given the distance and bureaucracy involved with establishing her legal status, it took several years for confirmation to reach Peru that she had not, in fact, ever taken orders officially. At that point, she was urged by the new Bishop of Peru to take permanent vows in the convent in which she was temporarily housed, but Catalina pushed back. She writes, “I told him that I had no order nor religious obligation and that I was trying to get back to my native land where I would do whatever seemed best for my salvation.”

Catalina was one of the first in the long, unfinished fight for equal pay. (Source)

What seemed best to her for her salvation, apparently, was to see if she could get a pension from the Spanish court for serving as a soldier all those years in the Indies. This took a fair amount of work. She needed to prove her case–not that she was a woman (for that had already been established), but that she’d been a good soldier and worthy of the same treatment as her male compatriots. This is when many of her past patrons, battalion leaders, and others came forward and vouched for the character and battle-worthiness of Alonso (or whatever name she had been fighting under when she was in their service). Since none of them had known she was a woman when she served with them, they were initially baffled, but many supported her cause.

Wherever she went, Catalina attracted great crowds. This is in large part because as soon as she left the convent, she took up wearing men’s clothes again, and people couldn’t contain themselves from ogling at the “Lieutenant Nun,” as she had come to be called. Her fame was such that when she traveled to Rome, she was granted an audience with Pope Urban VIII, whom she asked for a special papal dispensation that would allow her to live out her life as a man. This was a brilliant strategy–if he said yes, then she’d essentially be considered legally male in any Catholic country. He did. Catalina relates his response:

Pope Urban VIII is better known as the man who indicted Galileo, but he turns out to have been remarkably trans-friendly.

His Holiness showed himself to be astonished by such a tale, and kindly granted me permission to continue my life dressed as a man, charging me to live honestly henceforth and to abstain from offending my neighbor, attaching the threat of the wrath of God to his order, “Non Occides.” [Latin for “Do not kill.”]

What I think is particularly interesting in Catalina’s account is that the Pope seems not to be overly concerned with her gender identity, but rather, gives his attention to her propensity for murder and mayhem. (And rightly so, I might add.) In fact, the implication seems to be that “living honestly” for Catalina would mean living peacefully as a man. It’s a remarkably mild, even positive reaction.

From this point on, Catalina, or rather, Don Antonio de Erauso, as she was now legally known, became a minor celebrity, fêted by Cardinals, princes, and the like at every turn. Catalina ends her autobiography on a happy note with typical zest, with an anecdote in which she deals with some would-be hecklers. These are literally her last words:

While strolling along the wharf in Naples one day, I perceived the loud laughter of two girls who were chatting with a couple of boys. We stared at each other and one said to me, “Where to, Lady Catalina?” I answered, “To give you a hundred whacks on the head, my lady whores, and a hundred slashes to whomever may wish to defend you!” They shut up and slipped away.

If that isn’t the very definition of having cojones, I don’t know what is. Would to God that all haters were as easily and forcefully shut down.

If Catalina were alive today, she might express herself like this. (Source)

Catalina/Antonio eventually returned to the Indies (modern-day Mexico), where she set up an import/export business and died “an exemplary death” in 1650 in Veracruz. (13) To the last of her days, she lived as a man. As far as I can tell, she was the first and only person ever to receive papal dispensation to live as another gender. (14)

And with that, I rest my case. Model Spanish cavalier (with all the good and bad that entails). Lesbian heartbreaker. Early trans success story. Despite, or even because of, her many flaws, Catalina de Erauso should enter history textbooks (and classrooms) as an early “badass queer.” QED.

***

- This is an English translation of Catalina’s Spanish moniker, given to her by her contemporaries, “La Monja Alférez.”

- It has been very difficult to figure out which gender pronoun to use when speaking about Catalina and her male alter-egos. On the one hand, most scholarship refers to Catalina as “she,” and Catalina herself was insistent that she was, indeed, a woman. On the other hand, she herself spent most of her life dressed and living like a man, and clearly (and on more than one occasion) pled, ultimately successfully, to be treated as a man, complete with the use of an alternate name. Switching back and forth between “she” and “he” for Catalina and her various male alter-egos might make things a bit too complex for readers to follow, so I reluctantly am going to go with the scholarly crowd here. However, I do this with quite a bit of unease. I also might change my usage if I were teaching Catalina in class, since I tend to follow modern gender pronoun and vocabulary usage when working with teenagers. For more of my thoughts on why this is an especially important point for teens, see my note on my use of words like “gay,” “trans,” “genderqueer,” etc. from the first note in my last post. Having a commonly accepted English-language gender neutral pronoun would make things so much easier. *Deep sigh*

- The concept of “epistemicide” or the annihilation of non-Western (particularly indigenous) systems/paradigms of knowledge is one that is increasingly important in academic work on the colonial and post-colonial eras. Even the World Bank now makes use of the concept when trying to preserve indigenous farming and medical knowledge. It’s beyond my purview to really investigate this theme closely here, but I do think it’s interesting to note that Catalina finds her opportunity not in the Old World, where she was born, but in a place that is at the epicenter of a shift in world systems, where identities in general are to some degree both more fixed (as in the designation of people as being “pure” Castilian vs. “mestizo,” etc.) and more fluid, as the “wild west” setting of her tale makes clear. I also think it’s important to note that Catalina, as a Spaniard, enjoyed privileges not available to many indigenous or even mestizo individuals, and so it may have been easier for her to “pass.”

- All the quotes from and autobiographical information about Catalina are taken from her book, “The Autobiography of Doña Catalina de Erauso,”an English translation of which can be found here online.

- Catalina herself gives her birthdate as 1584, but her baptismal certificate would seem to indicate it was 1592.

- Catalina used a variety of names throughout her life, a few of which were Pedro de Olive, Francisco de Loyola, Alonso Diaz Ramirez de Guzman, and Antonio de Erauso. See the Spanish-language article in ARTEHISTORIA. “Monja alférez. Catalina de Erauso – Personajes – ARTEHISTORIA V2”.

- From what I’ve been able to tell, given my admittedly scant knowledge about Renaissance herbal lore, there certainly were (and are) herbal remedies used to “dry up” milk after miscarriages or unsuccessful births; how effective these would be at eliminating breasts altogether remains unclear to me. Or perhaps Catalina was using something that we now might recognize as an anti-estrogen. Or an acid-like concoction that literally burned her glands (perhaps explaining the pain?). Who knows. I should definitely take this moment, though, to add that I am NOT endorsing trying this at home, folks. Although herbs continue to be popular among some trans folk as a way of making a supposedly kinder, gentler transition, botanicals can be just as powerful as pharmaceuticals, and I would urge extreme caution when going it alone. Plus, we (thankfully) have WAY more options now than Catalina did.

- The original Spanish makes it clear that the person in whom Catalina confided and received a remedy from was male (“un italiano”).

- Catalina drops one other tantalizing hint that gender-bending behavior was perhaps more common during the Renaissance than we know. She writes that, upon hearing her confession about her identity, the Bishop stated “that he considered this the most remarkable case of its type he had ever heard of in his life.” [My italics.] A lot hangs on those three little italicized words. On the one hand, they could mean simply that the Bishop found Catalina’s story remarkable because it was more outrageous than the relatively common literary trope of cross-dressing. On the other hand, it could also imply that the Bishop knew of other such contemporary real-life cases of women dressing as men, and that among these, Catalina’s was the most remarkable. It’s impossible to know for sure, but the latter interpretation certainly piques one’s interest.

- Catalina’s military prowess has been the subject of much speculation. Some have conjectured that she was taught sword-fighting by her father, but this seems unlikely, since she entered the convent when she was four. It’s far more likely that she learned her military skills during her stints as a page. In other words, she was trained exactly like any other young gentleman of the period.

- I should note here that this is one of the places where the ugly social and racial realities of the time are made explicit in the text. The reason given by Catalina for her dislike of the young woman in question is that she is “very dark and ugly as the devil.” By Catalina’s own account, the girl was the daughter of a woman who was herself the product of a mixed Spanish-Indigenous marriage. As a pure-blood Spaniard, Catalina/Francisco was therefore situated much higher up in the colonial apartheid system, and was clearly not above abusing her own privilege, marginalized (in some ways) as she was herself.

- There has been a certain amount of speculation over the years about whether or not Catalina was intersex (e.g., whether or not she really had two X chromosomes, or whether she actually was XY). Of course, barring a DNA examination of her remains (and we don’t know where she is buried), this will remain a mystery. What we do know, though, is whatever her genes, she at least appeared to the midwives who examined her to be a woman.

- This quote comes from a legal document (another relación) written in 1653 in Mexico, quoted here.

- This is of course, discounting the legend of “Pope Joan,” a supposedly female pope who lived in the Middle Ages. She is believed by nearly all modern scholars to be fictitious.

Are there certain groups that must be dominated or put down in order to achieve “realness” of a particular gender role? (e.g. The use of “bitch/ho” in certain rap subcultures to create a hyper-masculine African-American persona, or the class-based insult “ratchet” to cast aspersion on a woman’s femininity)

Are there certain groups that must be dominated or put down in order to achieve “realness” of a particular gender role? (e.g. The use of “bitch/ho” in certain rap subcultures to create a hyper-masculine African-American persona, or the class-based insult “ratchet” to cast aspersion on a woman’s femininity)